Sea stacks are fascinating geological formations that consist of steep, vertical columns of rock standing isolated from the mainland, typically found along coastlines. They form through a gradual process of coastal erosion, where the relentless action of waves, wind, and weathering wears away weaker parts of headlands or cliffs.

Formation Process:

- Erosion of Headlands: The process begins when the sea erodes the base of a headland, often through hydraulic action and abrasion, creating sea caves.

- Formation of Sea Arches: Over time, the erosion enlarges these caves, eventually breaking through to the other side and forming a sea arch.

- Collapse of Arches: As erosion continues, the roof of the arch becomes unstable and collapses, leaving behind a free-standing column of rock—this is known as a sea stack.

- Ongoing Erosion: Once formed, sea stacks continue to be subject to erosional forces. Over time, they may become thinner and eventually collapse themselves, forming smaller rock formations called stumps.

Characteristics:

- Material Composition: Sea stacks are typically composed of harder rock types, such as sandstone, basalt, or limestone, which resist erosional forces longer than the surrounding material.

- Height and Shape: They vary greatly in height and shape, often reflecting the type of rock and the extent of erosion they've undergone.

Importance and Appeal:

- Ecological Significance: Sea stacks can provide important nesting sites for seabirds and are often surrounded by rich marine ecosystems.

- Tourism and Recreation: Their dramatic and isolated appearance makes them popular tourist attractions and subjects for photography. Many stacks are also favored by climbers eager to tackle their challenging heights.

Cultural and Mythological Associations:

Sea stacks frequently feature in local legends, mythologies, and folklore, often linked to stories of giants, ogres, or deities, reflecting their imposing and mysterious presence in the landscape.

Here are some of the most notable and iconic sea stacks around the world:

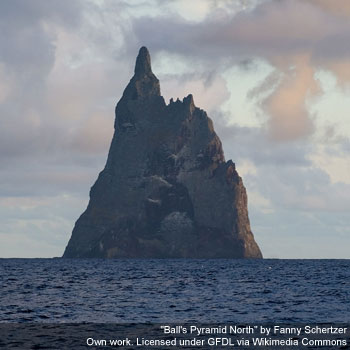

Ball’s Pyramid, Australia

This, the tallest volcanic stack in the world, can be found southeast of Lord Howe Island in the Pacific Ocean and is part of the Lord Howe Island Marine Park. It is 300m (1,844ft) high, 1,100m (3,600ft) in length and 300m (980ft) across. With its long, pointed section at the top it resembles a hand with outstretched finger, pointing towards the sky.

In 2001 an inhabitant was discovered clinging to the stack: a large species of insect, known as a tree lobster or Lord Howe Island stick insect. This insect had been believed to be extinct 80 years ago, due to rats which had been introduced to the larger islands. Scientists captured several of them for a breeding programme, with the hope that they may be introduced to the mainland.

Dun Briste, Ireland

Dun Briste, measuring about 50m (165ft) in height, stands 80 m off Downpatrick Head in Knockaun, east of Ballycastle. Here the Atlantic has gouged a massive bay from the huge cliffs which have been scoured of vegetation by the relentless winds.

It is a popular destination for birdwatchers, observing and recording the varied species nesting and visiting the stratified face of the stack. In May and early June the sea-pinks come into bloom and transform it into a sea of colour.

Legend tells of an ogre named Geodruisge who lived where the stack now stands. This nasty character often made life difficult for St Patrick, who prayed regularly at the church on Downpatrick Head. In exasperation the saint prayed for some barrier to separate him from the tyrant and the following morning the stack was found with the ogre’s house on it. He had no means of escaping and he subsequently perished.

Kicker Rock, Galapagos, Ecuador

Kicker Rock, or the Sleeping Lion, is a rocky stack on the western side of Isla San Cristobal, the easternmost island in the Galapagos archipelago. The gigantic rock, a popular destination for divers and nature lovers rises 152m (500ft) from the sea and is all that remains of a lava cone, now split in two. The mild currents, passing through the two rocks, attract hammerhead and Galapagos sharks and the rock itself is home to large colonies of sea birds.

Ko Tapu, Thailand

Ko Tapu lies off a pair of islands on the west coast of Thailand named Khao Phing Kan. It is a limestone rock about 20m (66ft) tall, with the unusual feature that it is narrower at the base than at the top. The diameter increases from about 4m at water level to 8m at the top, giving it a rather top-heavy look. The area used to be a barrier reef, but during tectonic movements it ruptured and the separate parts were dispersed and flooded by the rising ocean. In time the islands were eroded by wind, waves, currents and tides, thus forming some peculiar shaped rocks such as Ko Tapu. At water level constant erosion is obvious and it seems likely that at some point the stack will topple into the ocean.

A more fanciful story about the stack’s origin tells of a fisherman who had an unusually bad catch one day. He only picked up a nail with his net and in spite of continually throwing it back, he continued to catch it again. In a rage he took his sword and cut the nail in half, whereupon one half of the nail jumped up and speared into the sea, forming the stack we know as Ko Tapu.

Old Harry Rocks, Dorset, UK

These two iconic stacks are located on the Dorset coast, between Purbeck and the Isle of Wight, in the south of England and mark the eastern end of the Jurassic Coast. They consist mainly of chalk, with some bands of flint within them. As the coast suffered hydraulic action, caves and arches were formed; the tops of the arches then weakened and collapsed, leaving disconnected stacks. In the 18th century it was possible to walk from the mainland to Old Harry, the stack at the end nearest to the sea, but they are being constantly eroded and are an ever-changing feature. Old Harry’s wife was another stack which eroded so much that the top fell into the sea, leaving a mere stump behind.

Old Man of Hoy, Scotland, UK

The Old Man of Hoy is a 137m (449ft) sea stack close to Rackwick Bay, on the west coast of the island of Hoy, in the Orkney Islands and is one of the tallest stacks in Britain. It is a distinctive landmark from the Thurso to Stromness ferry; its red sandstone perched on a plinth of basalt rock, towering above the sea and resembling a human figure from certain angles. It was probably created some time after 1750, so is no more than a few hundred years old.

Sometime in the early 19th century one of its legs was washed away in a storm and by 1992 a 40m crack appeared in the top of the south face, leaving a large overhanging section that will eventually collapse as erosion by wind and tide continues. Winds are faster than 18mph for a third of the year and gales occur on average for 29 days a year. This, combined with the high-energy waves, due to the depth of the sea, ensure that erosion will continue.

The stack is popular with climbers and was first climbed by mountaineers Chris Bonington, Rusty Baillie and Tom Patey in 1966 and in the following year Bonington and Patey were joined by Joe Brown, Ian McNaught-Davis, Pete Crew and Dougal Haston, repeating their original route for “The Great Climb”, a live BBC 3-night outside broadcast which attracted around 15 million viewers. There are 7 routes up the stack and as many as 50 ascents are made each year.

Reynisdrangar’s Needles

These are basalt sea stacks situated under the mountain Reynisfjall, near the village Vik i Myrdal in southern Iceland. The needles are 66m tall at their highest point. According to legend they were formed when two trolls tried to drag a three-masted ship to land, but when daylight broke they were turned to stone. There are 3 main rocks; Skessudrangur and Landdrangur are the trolls, while Langhamar is the ship. There is also a local story about a monster who lived in the caves for many centuries, but he seems to have perished after a landslide over 100 years ago.

Risin Og Kellingin, Faroe Islands

Risin and Kellingin are two stacks just off the island of Eysturoy in the Faroe Islands, close to the town of Eioi. The name means The Giant and the Witch and refers to an old legend about their origins. The story is that the giants in Iceland were envious and decided they wanted to own the Faroes, so the Giant and the Witch were sent to bring the islands back. She tried to tie the islands together and push them onto the giant’s back, but part of the mountain split off and they found it too firm to move. As they struggled on during the night, dawn broke and a shaft of light turned them to stone.

The Giant (Risin) is 71m (233ft) high and is further from the coast while the Witch (Kellingin) is the 68m (223ft) pointed stack, nearer the land, standing with legs apart. Geologist predict that sometime in the next few decades, Kelligin will fall into the sea during the winter storms, following the section which broke off at the beginning of the 20th century.

Tri Brata, Russia

This trio of scenic stacks lie at the entrance of Avacha Bay and are seen of as a symbol of Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, the main city of Kamchatka Krai, Russia. The Russian name literally means “Three Brothers”, who, as legend has it, went to defend a town from a tsunami and were turned into pillars of stone.

The Twelve Apostles, Victoria, Australia

This is a collection of limestone stacks just off the shore of the Port Campbell National Park. They are a popular tourist attraction with around 2 million visitors per year and helicopter tours are available from the visitor center on the Great Ocean Road. Currently there are 8 apostles left, suffering, as they do, from constant erosion by the extreme weather from the Southern Ocean. It is expected that as this erosion continues more spectacular stacks will be formed from the ever changing faces of the headlands.